How the Noise node works¶

Nodes¶

The Noise* nodes works like other Uniform* nodes: they produces a

deterministic noisy signal which can be made available to the shader when

attached to the associated Render or Compute.

In the case of the NoiseFloat, the shader obtains a float sample

corresponding to the noise signal at a given time t. Similarly, NoiseVec2,

NoiseVec3 and NoiseVec4 will respectively provides a vec2, vec3 and

vec4 to the shader, where each component of the vector provides a different

signal with the same parameters.

The node themselves can not be used to create advanced patterns/fractals or even display a waveform within a shader because there is only one random value at a given time. On the other hand, it can typically be used to “wiggle” an object or a parameter.

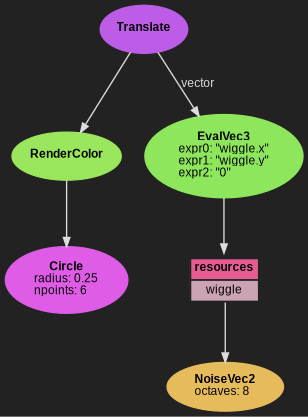

import pynopegl as ngl

@ngl.scene()

def wiggle(cfg: ngl.SceneCfg):

cfg.aspect_ratio = (1, 1)

cfg.duration = 3

geometry = ngl.Circle(radius=0.25, npoints=6)

render = ngl.RenderColor(geometry=geometry)

# Extend 2-dimensional noise into a vec3 for the Translate node using EvalVec3

translate = ngl.EvalVec3("wiggle.x", "wiggle.y", "0")

translate.update_resources(wiggle=ngl.NoiseVec2(octaves=8))

return ngl.Translate(render, vector=translate)

This mechanism could be implemented fully in GPU, but a GPU hash function can

be costly, difficult to get right, and hardly shared between pipelines. Having

the Noise builtin and CPU side allows a fast random generation as well as

sharing the signal between different branches. It gives shader a simple and

efficient source of noise that can be used in various creative situations.

Seed¶

Behind the scene, there is only one signal of noise generated. In order to make

different signals, the Noise*.seed parameter can be used. In practice, the

seed acts as an offsetting of the time t (in seconds), meaning you likely

want to keep seeds relatively apart from each other.

That same mechanism is used internally to decorrelate components in the

NoiseVec2, NoiseVec3 and NoiseVec4 nodes, using the seed parameter only

as base seed (the first component).

Algorithm¶

Random source¶

At the most elementary level, we generate random values from x-axis values. The

hashing function we use is lowbias32 from Chris Wellons, converted

to a float between 0.0 and 1.0. This hashing function makes sure that for

a given integer (the lattice / integer coordinate), we will always provide the

same float value with a uniform distribution.

We can not use a PRNG because it relies on a state where we need

determinism (for one coordinate, we always want the same random value).

LCG are a sub-classes of PRNG where the state is actually the returned

value. But even then, we can not re-use the previously returned value since we

need seeking; that is the ability to get the random value associated with our

integer coordinate. Trying to feed a PRNG/LCG with our coordinate instead of

the expected state would be equivalent to changing the seed at every call, and

this creates an important bias in the random distribution. This is the reason

why we need integer hashing instead. lowbias32 has been derived from an

advanced generator and was evaluated to be extremely good.

Random signal¶

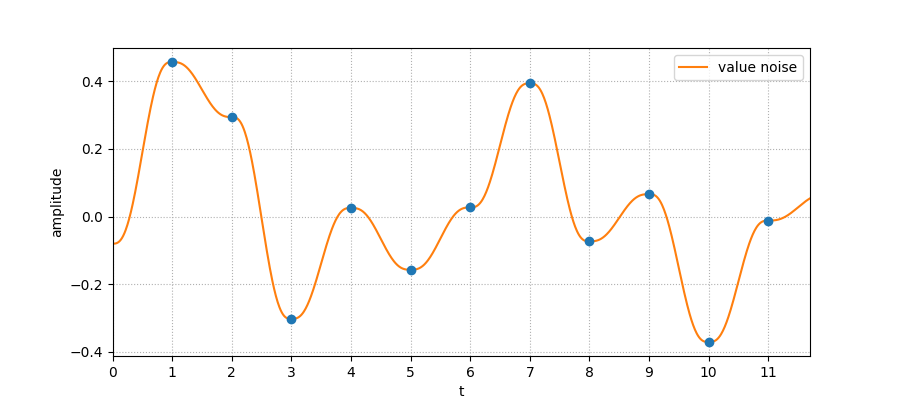

Using these random values as “key frames” and interpolating between them would give us a Value Noise, as illustrated below:

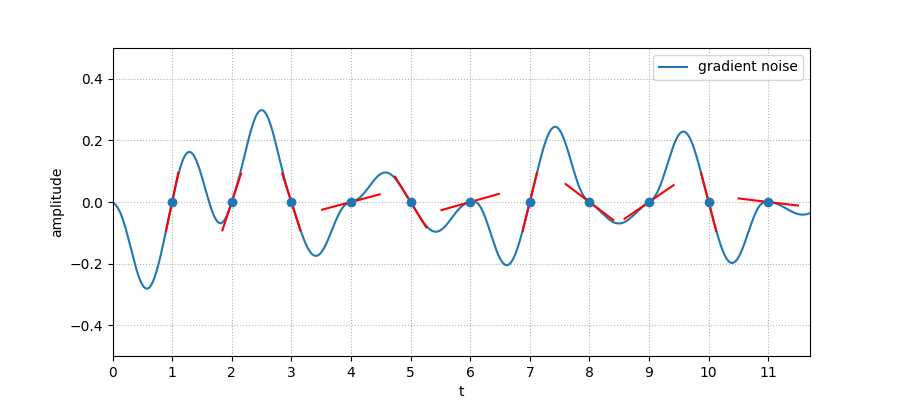

The patterns generated in such a way are not desirable due to the variation in frequencies: when points are close the frequency is low, and can suddenly fluctuates. So instead of using the random values as the noise signal itself, we interpret them as gradient: this is the Gradient Noise, used in the popular Perlin Noise. In our case, since we use a 1D signal, it looks like the following:

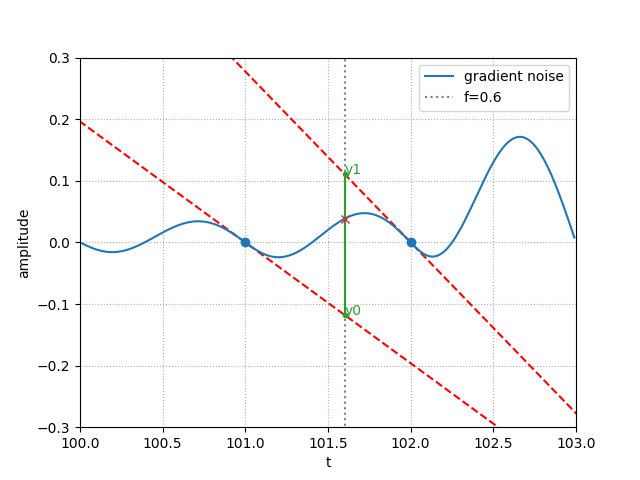

Random values of 0 and 1 (the output of the hash function rescaled into a

float) respectively correspond to a tilt of -45° (-π/4) and 45° (π/4).

The interpolation between 2 gradient points works that way: for a given time

value t between 2 gradients, we obtain two y-axis coordinates by extending

the line of each of these gradients. The signal value at t lies somewhere

between these 2 points: y0 and y1 are the boundaries of the interpolation.

f is used to represent the x-axis distance between t and each lattice

(where the gradients are located); we use it as an amount for the non-linear

interpolation (see next section for the formulas) to get the finale value.

Note: one important property of the gradient noise is that it passes through 0 at every lattice / cycle.

Interpolants¶

The two common interpolation functions are:

the Cubic Hermite curve,

f(t)=3t²-2t³(typically used in GLSLsmoothstep()) initially used by Ken Perlin in his first Perlin Noise implementationthe more modern (and complex) quintic curve

f(t)=6t⁵-15t⁴+10t³introduced in 2002 by Ken Perlin in his proposed improved version of the Perlin Noise, in order to address discontinuities in the 2nd order derivativesf"(t).

Both functions are available in the Noise*.interpolant parameter, along with

a linear interpolation f(t)=t which can be used for debugging purpose. It is

not recommended to use that one for another purpose because it will cause an

undesired output (flat curve) if the gradients are oriented the same.

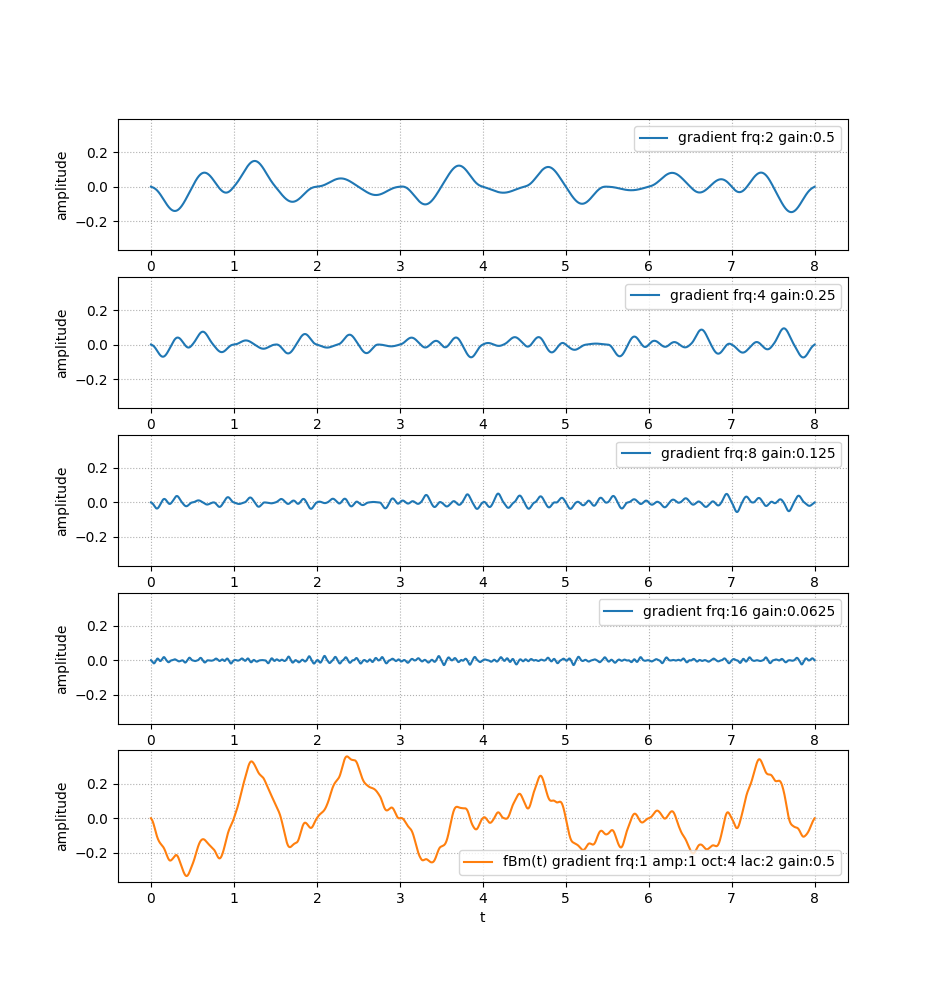

Accumulation¶

The finale noise is generated using a form of fractional Brownian

motion, which basically means multiple layers of gradient noise are

added together to create a refined pattern. The parameter controlling the

number of layers accumulated is Noise*.octaves.

With the standard parameters, each octave will see its frequency double

(Noise*.lacunarity=2) and its amplitude halved (Noise*.gain=½) from the

previous one. The gain is also known as persistence, and in its mathematical

form derived from the Hurst exponent. This gain/persistence/Hurst

notion refers to the same thing, which is the “memory” between octaves, or

self-similarity.

As stated earlier, the gradient noise crosses 0 on every lattice. Even when

cumulated with other frequencies, this pattern will remain if the lacunarity is

an integer. Using 1.98 instead of 2.0 can prevent this (of course, with

more than one octave).